Richard doing an overdub in the studio.

Stolen from Richard’s Website: Richard Emmet has composed music for feature films, television, radio, commercials, multi-media, the concert stage, ballet, and more than 40 audio books. His music has been placed in dozens of TV shows, including FBI Criminal Pursuit, As the World Turns, One Life to Live, Sesame Street, Dog the Bounty Hunter, and Bravo’s Fashion Show.

As a musician, Richard has performed in jazz orchestras, rock bands, chamber music groups, and Javanese gamelan ensembles on the east and west coasts.

In addition, Richard spent five years as an assistant to Frank Zappa.

Editor’s Note: Richard Emmet is far more fascinating than he realizes. I always feel a certain kinship when I see him at TAXI’s annual convention. We grew up in the music industry at the same time, but on different coasts. Our musical worlds were even farther apart yet equally influential on who we became later in life. —ML

Richard Emmet (left), Frank Zappa (right), and David Ocker (foreground) hard at work.

Where did you grow up?

I was born in Queens, NY, but I’m not sure why since we lived in Manhattan at the time. When I was 3, we moved to New Haven, CT. During my teens I got to see dozens of great bands when they came to town, including The Rolling Stones, Jethro Tull, Herman’s Hermits, Dave Clark 5, The Animals, Janis Joplin, The Zombies, Sam the Sham, The Lovin’ Spoonful, and many more.

Oh, and Michael Bolton was a friend and schoolmate. I lived in New Haven until age 19 when I left to study music at CalArts.

Do you come from a musical family?

I was the only one who played an instrument. But all of us – brother, sister, parents – were avid listeners, especially when the Beatles came along. I remember the whole family standing around the radio listening to “I Want to Hold Your Hand” when it came on, which seemed to be every 10 minutes or so.

My mother was a passionate opera lover. Me? Not so much. I find the tense, overly vibrato-laden operatic vocal style painful to listen to. Get Loreena McKennitt or Kate Bush to sing opera and I might change my mind!

How old were you when you started playing an instrument?

I began guitar lessons when I was 7. I think I was in 3rd grade when I got recruited into playing a guitar solo in a school play. It was a play about the Civil War and I had to play “I Wish I Was in Dixie” (land of cotton, etc.). Yikes.

When did you write your first song or compose your first piece of music?

The first piece I recall writing was inspired by the title of a Chick Corea composition called “Tones for Joan’s Bones.” It came out in 1968 so I must have been 15 or 16. The only detail I remember about my composition is that I gave it a ridiculously long, rhyming title. Shockingly, it’s not included in my BMI catalog.

At what point did you think that music could become more than a hobby?

This is the odd thing. At the point when I started thinking about my future, I never seriously considered any other option. It just felt pretty much set in stone that music was my path. It never occurred to me that this path might be strewn with occasional rocks, fallen trees, and other obstacles along the way. But had I known, I suspect I would have taken the same path nonetheless, though hopefully in smarter, more perceptive ways.

What instruments do you play, and which one would you say is your primary instrument?

Guitar is my main instrument. At one time, I was a good tenor sax player as well. (Charles Lloyd and Wayne Shorter were my tenor heroes.) In my teens I played guitar with the Quinnipiac Jazz Orchestra in New Haven one year, and tenor sax the next year. I abandoned the sax in my twenties, but I recently bought an alto sax in the hopes of resurrecting those lost skills. Holy cow, it hasn’t been easy! I must have had a lot more time to practice back then.

I also play keyboards rather poorly, but well enough to compose and produce my music with the indispensible aid of modern technology.

Almost forgot: I also played flute in the old days. Classical and jazz. But like the sax, I abandoned it as I got more involved in composition. However, there was a TAXI listing in late 2016 for flute music in any style. So in another attempted resurrection, I figured I’d give it a shot. Though I hadn’t touched it in more than 30 years, I still had my flute. How hard could it be? Turns out, it was very hard! I could barely get a sound out of the instrument, and not just because of the green stuff growing inside. Eventually, I managed to produce enough passable long tones that, when tastefully drenched in reverb, turned into a decent ambient piece. And it was forwarded! Talk about hard-won victories.

"[Zappa] had an unmistakable magnetism that, when combined with the clarity of his intentions and the force of his personality, made him a natural and effective leader. Refreshingly, however, he had no need to brag or blatantly call attention to his gifts."

I know Kenny Kerner interviewed you some years ago for TAXI, and he asked you about your time working with Frank Zappa. It’s such a cool and unique story that I’ve got to ask you to tell it again. Do you mind?

I don’t mind.

How old were you at the time, and what were you doing with your life?

It was 1978 and I was 25. I had graduated from Cal Arts the year before and was sharing an apartment on Venice Beach with a community of fleas and roaches. In hindsight, it’s amazing that there was actually a time when $160/month for an apartment that was 20 ft. from the beach seemed outrageous! Anyway, to support myself, I was playing guitar in a small house band for an equity-waiver theater company in East Hollywood.

How did you get the gig with Zappa?

I had taken a class at CalArts on musical calligraphy. Basically this was a fancy, pre-computer method of creating music notation by hand that bore a passing resemblance to professionally engraved printed music. A fellow CalArts grad, David Ocker, had taken the same class. At some point after we graduated, I learned that David had landed a job with Zappa. I’ll continue, but first a slight digression.

There were a number of people in Los Angeles in those days who, often quietly, made enormous contributions to the musical life of the city and beyond. One such person, as most of us know, was John Braheny.

Another was the late Judy Green, a friend to composers both famous and unknown. Judy’s shop was located on N. Cahuenga in Hollywood and offered music supplies and reproduction services to individuals and institutions far and wide. It’s where we brought all the Zappa scores for reproduction and binding. If anyone is curious, check out the link below and learn about a wonderful woman and longtime benefactor of the musical arts. Without Judy Green Music, it’s unlikely I would have connected with Zappa.

https://www.jgmpaper.com/aboutus.html

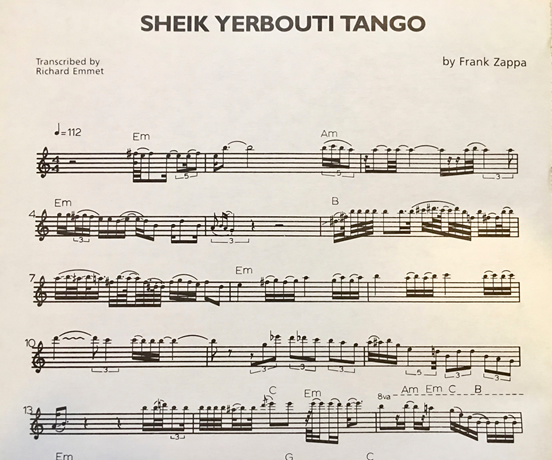

Back to the story: My friend David had posted a flyer in Judy Green’s shop advertising his music copying ability. Apparently Zappa saw or heard about the flyer. He called David and invited him over to talk about a possible staff position as a music copyist. David got the job, and when I heard about it a couple of months later, I asked him if Frank might need another copyist. David said he’d ask, and a couple of weeks later Frank called and invited me over. I drove to his house (now owned by Lady Gaga!) on Woodrow Wilson Drive in the Hollywood Hills and met Frank and his wife Gail. But instead of hiring me as a music copyist, he asked if I could transcribe a couple of his recorded guitar solos. He gave me a cassette and a ¼ inch reel-to-reel tape to work from and I methodically plowed through the complicated improvised solos. I returned several days later, handed over the transcriptions, and that was that. Here’s the opening section from one of the guitar solos I transcribed.

A couple of months later Frank called again and hired me as a fulltime music copyist. The job lasted about 5 years, from 1978 to 1983.

Wow, that’s mind-blowing! Musicians all over the world were awe struck (and still are) by Frank Zappa’s talent, vision, creativity, and uniqueness. Did you ever have to pinch yourself and wonder if the gig was real or just a dream?

I pinch myself now more than I did then! At the time, I knew I had stumbled upon a very special situation, but Frank kept me so busy, and the job was so narrowly focused, that I didn’t truly grasp the totality of who he was and the impact he would have on the world and on my life. It wasn’t until after his death, which hit me surprisingly hard, that the significance of the experience began to fully sink in.

I have lots of memories and impressions of Frank, some of them described on my website, so I’ll try not to repeat myself. Suffice it to say that he embodied a rare and potent mixture of intelligence, creativity, work ethic, humor, cynicism, irreverence, perceptiveness, fearlessness, and surprising kindness. He had an unmistakable magnetism that, when combined with the clarity of his intentions and the force of his personality, made him a natural and effective leader. Refreshingly, however, he had no need to brag or blatantly call attention to his gifts. A half an hour in his presence made it clear that you weren’t in Kansas anymore, and this wasn’t your average human.

I don’t mean to suggest that Frank was a saint or was absent of flaws. Far from it, as I’m sure his wife Gail could have attested. But simply put, he was, without a doubt, the most staggeringly impressive person I’ve known or will ever know.

What was the gig like on a day-to-day basis?

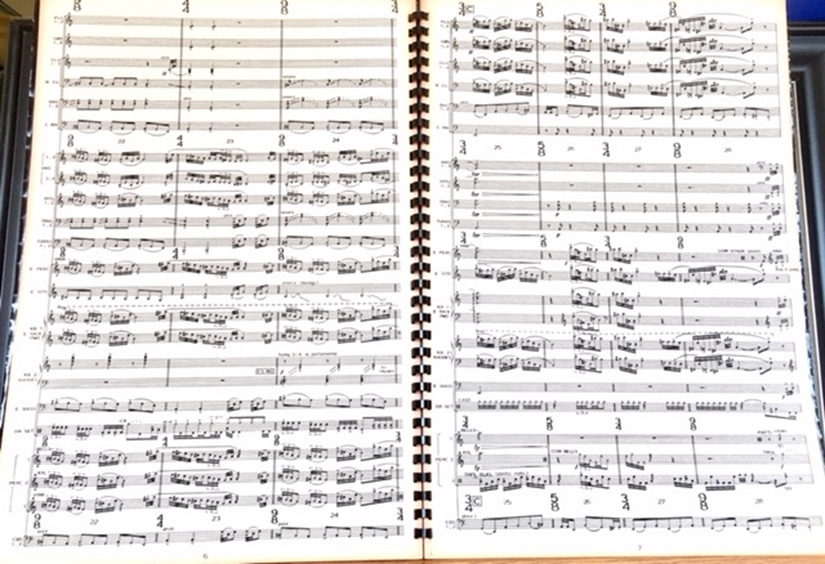

Frank wrote a ton of orchestral music and his scores were very detailed and often quite complex. He sketched the music in pencil on large staff paper, and when he was ready, I’d drive to his house and look at the new score, often 50 pages or longer. I’d take the pages back to my apartment, and begin creating a permanent score from his draft. It was an arduous process because each page began as a blank – yes, blank – piece of 13½ x 19 tracing paper. Frank wanted the score customized on a page-by-page basis, so every item in the score had to be inked onto the blank page. Staff lines, clefs, notes, and all the other elements of musical notation were individually drawn on each page. A single page could take a whole day to complete, which may be one reason the job lasted so long. Here are two pages from his Dog Breath Variations score, which is less complex than much of his orchestral work.

After the full score was finished, the copyists – David and I at that point – were then tasked with creating the individual instrumental parts so that each player or section would have their own sheet music to play from. It was a lot of work.

Often when Frank and I had finished discussing the score, I would hang around for a while and listen to new material he was working on (Valley Girl comes to mind). Sometimes we’d talk politics (I’d been collecting signatures for an anti-nuclear petition, but he refused to sign it). Often I’d listen to stories about his encounters with John and Yoko, Bob Dylan, and others. Dylan asked Frank to produce his next album, but Frank declined. He told me he suspected Dylan went through his address book and called him when he got to ‘Z.’

On a few occasions I observed him during the recording process, initially at studios in town, and later in his own home studio. Among my recollections: He stopped a take at one point because the “Leslie” effect on a keyboard part didn’t match its panning position at the punch-in. Another time he asked the drummer for a cymbal roll to cover an imperfect tape splice. Yet another time he asked the engineer to do a slow board fade on an extended marimba roll during a live take in order to have one less task to do during mixdown. These sorts of recording techniques are either commonplace or irrelevant now, but with my limited studio experience at the time, they were revelations to me.

I can totally relate to those techniques. I’m proud of being old school! Tell me more, this stuff is fascinating to me, and I hope to our readers as well.

I once brought over a recording of a 20-minute chamber/choral piece I’d composed that had gotten a recent public performance. He threaded the tape onto one of his Ampex 2-track recorders and listened intently all the way through, occasionally asking questions about a particular note or section. I had no idea back then what a huge deal it was to casually interrupt his work and take 20 minutes of his time in this way. However, he gave absolutely no indication of being inconvenienced. He seemed genuinely interested in what I was about musically.

My biggest regret (and proof of my cluelessness): Frank invited me to spend a Thanksgiving family dinner at his house one year, but I was a vegetarian at the time and politely declined. Yes, I’ve experienced moments of pure idiocy!

This might be hard to answer, but were there any profound takeaways on either a musical or personal level?

How much time do we have? Seriously, there were a number of takeaways. Maybe the one that has stayed with me the longest is an appreciation of effective language use. Frank was incredibly articulate, and he had a way of bending language to his will. Whether he invented entirely new words or used the ones the rest of us are familiar with, he was a master communicator.

The other profound takeaway has been a firsthand look at what a self-directed life and total commitment to your art looks like.

I’m friendly with Steve Vai, and he once told me that he got a call from Frank, and he was flown out to work with him—I think as a copyist—when he was really young. Did you ever work with Steve, or was that during a different time period?

I did work a bit with Steve. It’s funny – as far as I know, the only time my name has appeared in a book about Zappa came from a Steve Vai quote in which he commented about something I’d transcribed. Anyway, there was a time when Frank was thinking about forming a different type of band, possibly including me as one of the guitar players. As an initial step, he gave Steve and me a new piece to learn. We thought it would be useful to practice it together, so Steve came to my apartment a couple of times and we learned the piece. I recall that Steve, not surprisingly, played it a “little” better than I did. I remember him telling me, “Mute those open strings, don’t let them keep ringing” during fast passages.

Nothing came of Frank’s “new band” idea, to my profound relief, but it was fun getting to hang with Steve. We reconnected by email a year or so ago for the first time since the early ’80s. It was great to catch up!

I’m probably not going too far out on a limb here, but I’d guess that you’re a pretty meticulous person in all aspects of your life. Is that a blessing or a burden?

If only it were true! The burden is that I’m meticulous, primarily in just one aspect of my life: music. I tend to slave over every note, every detail of an arrangement, every lyric if I’m writing a song, every mix decision, etc., etc. My obsession with editing would make even Jason Blume (a strong advocate of rewriting) run for the hills. It’s a habit that makes my BMI catalog wonder if anyone’s home. I’m trying to break this habit while still producing work that sounds acceptable to me.

Is music your fulltime gig, or do you also have a day gig?

I have a day gig as a legal assistant in a law firm. I’ve been doing this type of work for almost 15 years off and on. I also have, along with my partner Margaret and an old friend in LA, a fledgling Amazon business selling plastic-free stainless steel water bottles and other non-plastic, eco-friendly items. Because of the dire consequences of plastic on the environment and on our health, we want to support the growing movement against its overuse.

Tell us about your family… how do you balance creating music, your family, and your day gig?

My family includes my two boys, Noah and Nathaniel from my former marriage, and Margaret and her daughter, Cara. Margaret and I have known each other since our teens, when we were involved for a time. We eventually had separate marriages (and attended each other’s weddings a week apart), had kids, and 40 years later got back together. Life is full of surprises.

Balancing family life, music, a day job, and a new business is a work in progress. The issue of time – how to use it, how much remains – is an ongoing concern. Certainly running your own business can be exhausting! Did you know that, Michael?

The short answer is that we do the best we can and try to maintain a sense of humor.

Don’t miss Part 2 of this interview in next month’s TAXI Transmitter!

Check out Richard’s website!