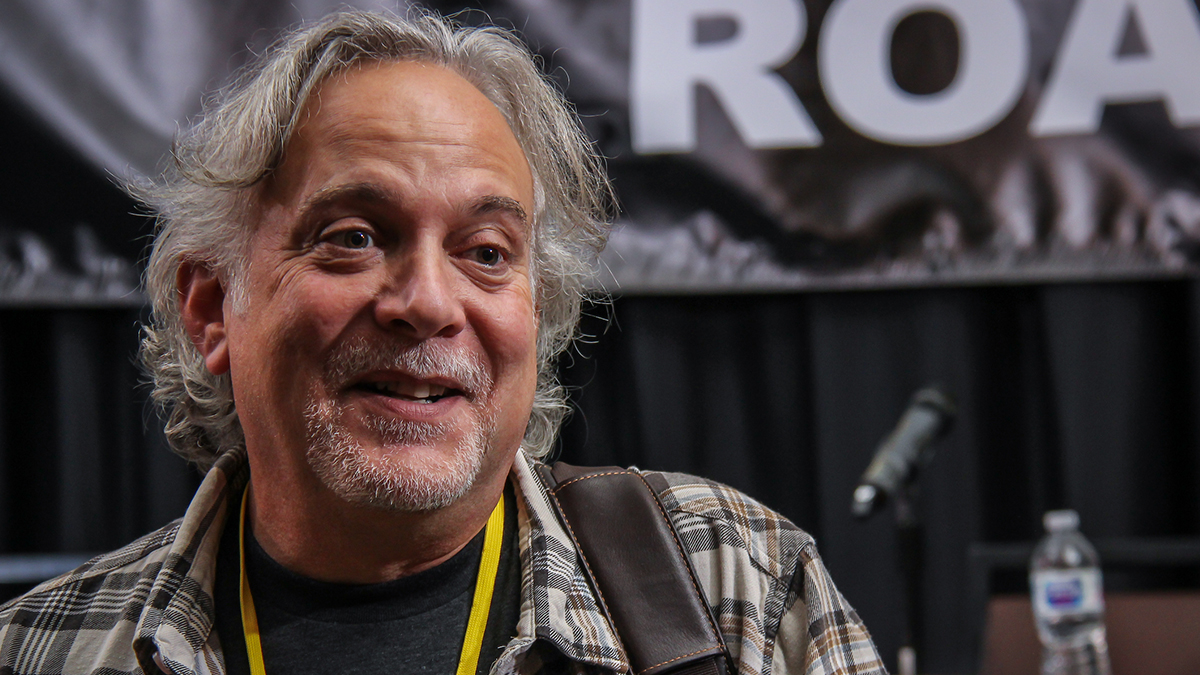

Interviewed by Michael Laskow during TAXI’s Road Rally, November, 2020

Michael Laskow: I’ve discovered over the last couple years that if I were a songwriter, I would be borrowing ideas from dialog in television shows or films—the best writers in the business. Deb and I watched Outlander. We binged all five seasons of Outlander in about a month—a lot of 3 a.m. mornings on that show. There were so many lines that were just beautifully written that it would inspire me… Sometimes I would just sit there with a Post-It note and write down what the actor just said, thinking it would be such a great title or concept for a song. Obviously, you’re not going to plagiarize or actually steal the dialogue, but if somebody says — I don’t have a great example — , “Home is where the heart is,” and you go, “Wow. That’s kinda cool, ‘Home is where the heart is.’” Someday, when it’s writing day, and you pull out your Post-It notes, “Home is where the heart is”… Anyway, these are the highest-paid writers in the business. If you’re gonna borrow concepts, grab them from the best.

Mason Cooper: Yeah, there’s that sort of phrase, you know, the old clichés. You know, there are only X amount of topics, right? Love, hurt, blah, blah, blah. Your job is to find a way of telling your story. When I lived in Nashville years ago, we used to hang out at Close Quarters; now it’s something else. The old joke used to be, if somebody behind you is sitting back in the chair at the restaurant table, they’re listening to what you are saying, because it’s where all the songwriters hung out. So, if you’re talking to somebody and someone is leaning back, they’re trying to hear what you’re saying to get an idea. “Oh yeah, ‘Home is where the heart is.’ What he said, I’m gonna write that song.” Someone is stealing your words… They get the idea, like, “Oh yeah, ‘Home is where the heart is.’” So that was the old thing, don’t let anyone listen in on conversations; they may take your conversation and…

But that’s important. Don’t let anyone do it to you, but you should do it to others. Find a phrase or some comment from a book or from someone on the street. Someone says, “Hey, Joe, remember me?” Well, that might trigger, “Oh, I’m gonna write a song about remembering my college days.” Whatever it is, whatever triggers you to have an idea. Keep your ears open, observe, and put it in your phone.

“Avoid samples. If you can’t create it, don’t use it. And don’t send it to me.”

I want to go back to process. We’ve only got about 10 minutes left. So now I think we’ve covered the whole process on TV, other than the actual licensing, which is basically reaching out to people, making sure that it will clear, meaning that there are no incumbrances, like it doesn’t have somebody whose sample is on it, or lead vocalist who is deceased who never signed off on a work-for-hire or something—all those little legal bugaboos that could take something out…and they can. And you could be right up against the deadline, you know. That thing is going to lock-picture tomorrow morning, and you haven’t heard back from this writer.

So, I’m saying all this to let people know, because I experience it all the time in my job, all the time: If you see a phone call and you don’t know the number, and it’s from 818, 310, 213, 212, any of the commonly used area codes from the big production centers, you should answer that call, because it could be Mason Cooper calling you trying to get clearance on something, and he’s got a lock it to picture the next day—final lock. And if he doesn’t get you, you’re toast. Is that a true statement?

Yeah, and the rights will be… Know who your co-writers are; know who your co-publishers are, who owns and controls the licensing on both the song and the recording. And if it’s work-for-hire artists you’ve got, you have to have them sign off. I mean if I’m going to do a license with you there’s an indemnification, you are liable, not me.

So, knowing your rights is really important. If you own both sides, publishing and the master recording side 100%, great, if you don’t, that’s OK also, as long as you know who they are. Don’t use samples; don’t send me anything with samples or use another sample from a recording. You know, hip-hop songs where there are 47 writers and 32 of those are on old songs that were sampled, and then there are 14 different publishers, we don’t have time for that—it’s too complicated. Avoid samples. If you can’t create it, don’t use it. And don’t send it to me.

Oh, I’d like to say this. Here’s the deal: If somebody says, “I’d like to use your song, but I only have X dollars,” don’t get upset at that, just say no, or say yes. It’s better to say yes. But don’t get upset; you have the right, you own the song, and we use the song… I’ve been dealing with this on a film I just finished, and it was a major producer who co-wrote the song that I’m using with an independent writer. They both had questions about the clearance sheet; they wanted to make sure that it was not exclusive. They’re always non-exclusive. If I use your song, you could use it in a hundred different projects. If I want it to be an exclusive use where nobody else can use it but me, I’m going to be paying you a whole lot of money.

Which they will do on some of those shows that are very music-driven, where they’re going to put out potentially like a cast album or something like that…

If it’s a main theme to a network show, they’re going to want to lock it in. But let’s say that it’s 99.99999%, non-exclusive. You are also—unless they specifically ask and have a transfer of copyright—they are not going to own your song. You own your song.

They’re just renting it.

We’re just renting it. So, the clearance is a short form, a one-and-a-half-page form that says, “If we use… You are not guaranteed we’re using it. But if we want to use your song, you will allow us to use it under these terms.” So, you’re giving us the permission, you are telling us, “Yes, you may use my song under those conditions and terms. Please keep me posted if you do end up using it in the final mix.” Now, before it’s released, you have to do a formal license, which is three or four pages long and really doesn’t say anything different, just more legalese, and then finish all whatever the terms are, if there’s a payment or whatever.

So, the clearance is the first step in the process where, “I like your song and I think I want to use it. I’m gonna ask for your permission to make sure I have 100% of the rights covered. If I use it, I’m allowed to use it, you’re not gonna say no.” But if you want to get offended that somebody says, “I want to use your song and pay you 14 cents,” don’t get offended, just say no. “No thank you. I’m glad you like my song, but no.”

But they should understand where you are coming from. Music supervisors don’t get to pocket leftover money that they’ve got in the budget. So, if they’ve got 5,000 bucks an episode for using music and they offer you 1,000 bucks, that means they’re probably going to license five songs at 1,000 bucks a pop. That’s just the going rate for that budget for that show. And you could always say, “Can we do $1,500?”

No problem to ask, because here’s what could happen, if you ask reasonably. If I said I have $1,000 for this song use in this episode, you’re right, I’m given $5,000, it’s a puzzle. I’d have to have five songs at $1,000. One might say, “Well, this is more featured [so I’ll have to pay more], but that restaurant is gonna have two songs that could be anything. I’m gonna pay those $500 each.” Whatever it is, I can make my puzzle fit. If you say that you really want $2,000 because there are four writers, by the time we split it up—a legitimate question, I’m either gonna say I don’t have it…

“But just know that music supervisors —for the most part— don’t have time to play games; we don’t need to win. We are given a pie, and we have to split the pie up amongst what’s needed.”

You’re not playing hardball saying you don’t have it; you just don’t have it.

Right. But if my director or showrunner at that point says, “I love this song,” then I might just go, “OK, you want $2,000; will you take $1,500?” But now I’m going to have to cut another song out and maybe find a library song [that’s less expensive] or a score piece or do something in there. So, I have to fit the budget.

It’s OK to ask questions. You know, I told my daughter this, “Everyone should be free to ask questions, as long as you [the person asking] accept the answer.” You might not like the answer, but again, if you don’t ask, you don’t get it. But just know that music supervisors — for the most part — don’t have time to play games; we don’t need to win. We are given a pie, and we have to split the pie up amongst what’s needed. That’s it. I mean, it’s kinda that simple.

“We’re usually close to 100% of those songs that I get from TAXI are right within that target. I’ve used some, I haven’t used some, but none of them are a waste of time to listen to because they’ve been targeted.”

All great stuff, Mason. People in the Chat have said, “This is gold,” and they’re absolutely right. And for you and I, we go out to dinner or something, and this is the conversation we have, the two of us. We could talk endlessly, and hopefully there’s benefit in what comes out of these conversations.

Yeah. You said something earlier on about something that I have to “present.” Music supervisors usually do not make the final decision. But you develop relationships with the director or showrunner over time if you rely on us. Sometimes they’ll give me a gimme. You know, trust me on this. Maybe for one of the scenes where they don’t care too much, or it’s a background [song]. But yes, you are presenting, your members will present things through TAXI, who knows us well enough to winnow things down. When I get a playlist from TAXI, it’s whittled down, and we’re usually close to 100% of those songs that I get from TAXI are right within that target. I’ve used some, I haven’t used some, but none of them are a waste of time to listen to, because they’ve been targeted. I may like these, but now I have to go to my director. On a TV show, I can go to the showrunner, but then the network is gonna have something to say. So, there are a lot of decisions that go along the way, so that is why it’s patience, patience, patience! Even if we like your song, let it go through [the process] and hope that it sticks at the end.

We’ve only got two and a half minutes left, and we haven’t talked about film. And we literally have a real two and a half minutes.

Let’s start from the beginning. [laughter]

No, let’s not. [laughter]

Almost everything we said is true for film as well as TV. The timeline is much broader, but most of the music, unless it’s performed on camera, it’s still post-production. So still at the end, if they’re going to shoot for 20 days or three months or six months, and pre-production was months before that, for the most part it’s still post-production. Once they have filmed and I see footage, I now can take songs and start to use and edit songs in and go, “Oh, this type of song with the tech track will start working.” We now have about eight weeks of that, then the picture is locked. Then I probably have about six to eight weeks to work with a composer and songs until we go to final mix.

Who is harder to have as your boss as music supervisor? A director on a film or a showrunner on a TV show?

A producer on a film, because they have very little knowledge, experience, and sometimes say, unless they have the best drama film. But they have opinions, and they will come in.

The investors aren’t so hard to deal with. It’s usually the other producers that just think, “I helped shepherd this through; I put this together, and I had this vision.” What I have to do is navigate. Is the director a hired gun on a film? They usually aren’t, but they can get treated that way. Is their contract a DGA contract? Would they have final say on the final cut, or do theynot, where the producer has the final say?

I am just recently out of a project where I had to navigate that and say, “Who’s the boss?” Because it is what I call a camel. Do you know what a camel is, Michael? It’s a horse made by committee. And I had to navigate who was the final boss, because I can’t make everybody happy. So that is a difficult process. It’s usually the director of the film.

“Don’t spend too much of your time trying to hit the studios with major films, because they already have their relationships; go to indie films.”

I’ve gotta jump. Remind me the next time we talk outside of this context. We’ve been working with a young independent film producer named Bernie, and the two of you guys will love each other. He does small-ish films, but they’re getting bigger and he’s getting more and more traction. You should just know each other. You guys would work so well together.

Indie films, and your people should be hitting indie films. Don’t spend too much of your time trying to hit the studios with major films, because they already have their relationships; go to indie films. Our budgets are lower, but we have more access, and they allow us to discover unknown songs, unknown artists. They don’t care who the name is on it, it’s about the song that works. Your members have better access to the independent films and TV productions.

Yeah. We hit it out of the ballpark. Every time we work on an indie film we usually are getting now seven, eight, nine songs in every indie film through running TAXI listings. Most publishers can’t pull that off.

Anyway, Mason, you are the best. Not only have you become a dear friend over the last few years, a lot of that friendship is built on that I have tremendous respect for your knowledge of how the industry works, and we just get along on a personal level, but I love sharing you with my people.

I appreciate it, and I appreciate what you do for all of your people.

I can’t wait to see you in person. Hey, is the breakfast place open by you? Can we go eat outside there, yet?

Yes, they’ve expanded into the garden.

Let’s do it some Sunday. I’ll bring Deb up and the four of us can go out. I need to get a life.

Alright, ladies and gentlemen, Mason Cooper. Thank you!